My playbook on going from law to tech

On law firms, startup culture, why, and how you could jump ship.

A disclaimer-ish note

All career advice is generally useless, and generalized career advice is worse. Without personalized context and background information factored in, it’s hard to use any of it to decide what to do and how to do it. This piece is based on my relevant learnings and observations in the last couple of years. I write not for everyone, but only for those that have or will have similar goals and ambitions as I did when I was in law school. If that is you, I hope this helps you, and I’ll be happy to help in any other way possible as well.

How I know what I’m talking about?

I studied law at NLU Delhi (2015-20), interned parallely at the Supreme Court from 2019-20, but then quit six months before graduating to continue with my original plan, i.e. to work in tech. I worked with the founders of Devfolio and Nanonets (YC W17) in 2020 and 2021 respectively, before quitting to join Superteam at the time of its founding in late 2021. I’ve since been part of the core team, and now lead the early stage crypto accelerator Superteam runs with FTX Ventures. With ups and downs, I made the transition from 50% lawyer to 0% lawyer, I wanted to, over the last 2 years.

Many people helped me along the way, either directly by replying to emails or indirectly via the similar pieces they wrote about their experiences. One such short essay was “From Law School to Tech” written by one such mentor (and now colleague) Akshay BD. It talks about why you should consider making the switch. This essay is a spiritual sequel, where I expand and write in some detail the tactical playbook that I would’ve loved to have back in the day of 2 years ago.

Why not work at a startup?

Working at startups is cool and different: Sometime around 2014, between Flipkart getting unicorn status and TVF’s since-lost show Pitchers coming out, “startups” suddenly became the cool thing to do for young people in India. Depending on what crowds you go around in, starting small tech companies, went from low status to at least medium-high over the last few years. Now, too many engineers want to become Founders, many MBAs want to do “Strategy” at startups, and even lawyers, media persons, and high school students are doing some make-believe version of starting up like starting a blog, or a shop with a website to call themselves its Founder (before having to use that as experience to get a job). Some will take it to the next step and even join startups later. Even though probably good in the long term, many even today are doing it for negative imitations reasons, i.e. to continue being different from those around them, and forcing themselves to go the other way. If you think that’s you, you’re likely to regret it down the line until you unlearn a lot of this.

TVF Pitchers (2015). Less accurate today, but good time capsule on 2014 startup culture in India. Your current work life is “horrible”: It’s true that many law firms and litigators make entry-level associates work insane hours, often for mediocre pay, and even lesser respect for your free time. In the last decade, outside perception of life at startups has been overly glorified. Everyone imagines colorful Googlesque culture, with unlimited cold brew, WeWork-ified industrial chic interiors, hobby time, first name culture, and hoodies (the last two bits are true though).

Do proceed with caution if you have been susceptible to this as well. It is true that working at a startup is very different; with an almost maniacal obsession for casual clothing, remote work friendliness, time, and locational flexibility — work might actually seem more “chill” and liberating. But these are half-truths.

They make the work required seem much less hard than it is (and that's maybe why everyone over-emphasizes the good bits) when it is in fact much harder. Law firms firm are “default alive” businesses. You contribute, but your contribution is not remotely what keeps the lights on. Working at an early-stage startup is more similar to a private equity team deployed at a target company to bring out a turnaround in a failing business. Except that a startup has no history of success, a fraction of the resources, and no reputation to easily get A-players. This is an incredibly hard task, and very few succeed. Working at any startup with even a chance of success will take over your entire life. Late nights, weekends, late nights on weekends, it’s all game. The next time you see a startup founder on LinkedIn talking about work-life balance, see if it’s really even a startup anymore.

To make more money: If you want to make more money than your current job, think very carefully before you join a startup. In the bull run of 2021, you might have been seeing LinkedIn posts about salary inflation, insane perks, referral bonuses, and BMW super-bikes for new hires. This is all true in some sense, limited to a specific set of overfunded, already successful, or batshit crazy companies. Highly paid employees at early-stage startups are more or less a blip in the recent past.

For years, new joiners have often taken pay cuts relative to their existing jobs and welcomed the upside potential they get with higher equity ownership instead. Working at a startup is a wealth-building exercise. You compress larger companies’ many decades of work into a few years of very hard work and go from default dead to a real, default-alive business that makes money of its own. The real value lies in the equity, so picking a workplace is more similar to picking a company to invest in, except that you will invest with all your time instead of money. Your chances of becoming exponentially wealthier working at a startup are probably the same as becoming so from purely investing in general, i.e. very low. To find companies with upside left in them you need to find and judge companies that are both very good, and undervalued (or not hyped up). Even professional venture capital investors who do this for a living are not very good at this. Learning this, if at all, takes years so you’re mostly left alone with your beginners’ luck. Even if you do find a job at a startup that pays a lot, or one that has its equity value growing year over year, startups individually are still very fragile. You’re susceptible to more agile competition, market sentiment, macroeconomic conditions, and even regulations. Attrition is high, not only do people burn out and leave, but also because people get fired very often. If you have a family to support, if your downside isn’t covered, don’t have the flexibility to go through a financial dry period, and can’t afford to be jobless for a few months in case the worst happens, do not join a startup. When was the last time there were layoffs at law firms?

Why work at a startup?

If you’re reading this, you’re probably the kind who already knows they want to work at a startup. On the off chance, you’re looking for positive reasons (to convince someone else), there is only one — experiencing nonlinearity, in everything.

…but what is non-linearity?

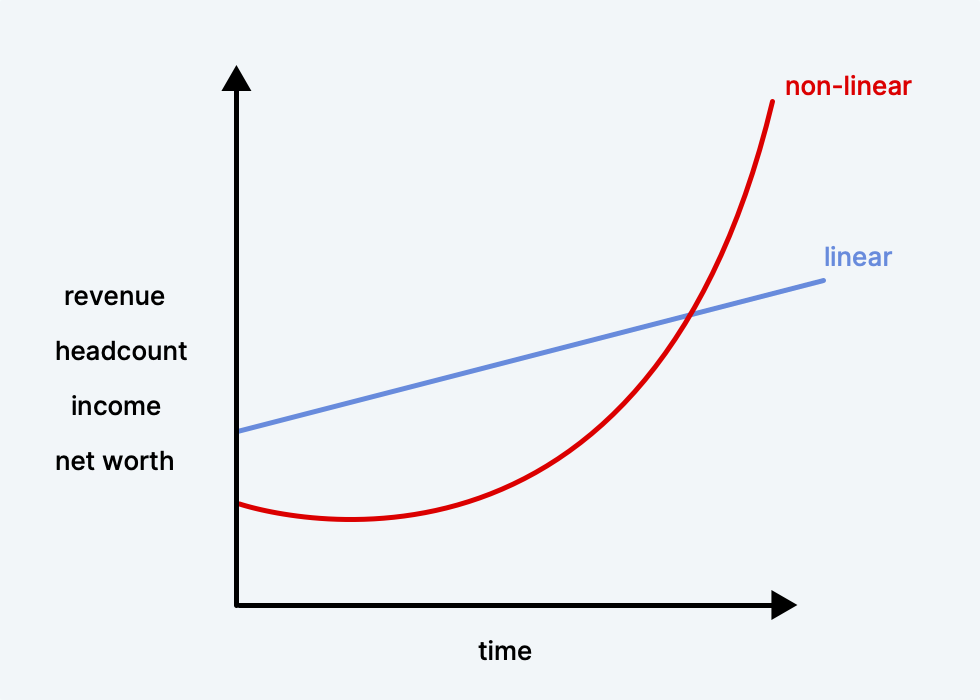

Law firms and legal practices are service-based businesses. Like all others in that same category {{examples banking investment banking auditing etc}}, they have some standard characteristics. They’re (1) profitable from day one, (2) do boutique, customized, client-specific work, and (3) have output (and revenues) more or less linearly linked to their headcount. When they’re successful, they also end up having a very similar, steady pace at which they grow year over year.

Startups are very unintuitive and very different from most of the kinds of “work” that existed before. They’re not services (law firms), self-employment (legal practices), large businesses (manufacturing), or even small businesses (grocery stores). It’s a category of its own. Small businesses and large businesses are both “businesses” but generally across their lifetime's scale correlated to the size of their initial investment. Startups are different because they start very similar to small businesses, if successful, end up as something similar to large businesses, in a fraction of the time. They don’t start out as profitable, aspire to have exponential revenue growth rates, and scale up to hopefully play in the big leagues.

This has interesting consequences which make working at a startup very different (which Marc Andreessen talks about in a related essay):

You’ll get to do lots of stuff. There will be so much stuff to do in the company that you’ll be able to do as much of it as you can possibly handle. Which means you’ll gain skills and experience very quickly.

You’ll probably get promoted quickly. Fast-growing companies are characterized by a chronic lack of people who can step up to all the important new leadership jobs that are being created all the time. If you are aggressive and performing well, promotions will come quickly and easily.

You’ll get used to being in a high-energy, rapidly-changing environment with sharp people and high expectations. It’s like training for a marathon while wearing ankle weights—if you ever end up going to a big company, you’ll blow everyone away. And if you ever go to a startup, you’ll be ready for the intensity.

Reputational benefit. Having Silicon Graphics from the early ’90s, Netscape from the mid-90s, eBay from the late ’90s, Paypal from the early ’00s, or Google from the mid-00s on your resume is as valuable as any advanced degree—it’s a permanent source of credibility.

All these reasons to work at a startup arise out of this rapid growth and the lag it has on up-skilling and recruiting (sometimes limited by natural factors such as eligible people not being born yet). This leads us to the biggie.

Ownership: why it really matters

At the end of the day to make it all worth it, you need the financial upside (or at least a chance to have high upside). In traditionally managed companies (and in Economics 101) people involved with a company are separated into labor and entrepreneur. The former provides services to the company to earn wages, and the latter invests capital into the company and makes all the upside. Startups operate differently, in what a friend calls Silicon Valley Management Style, where the lines between both a blurred since even employees hold shares in the company capturing the same exponential upside as the investors and the founders (even if not as much).

Even if your law firm’s revenue were to start growing 100% year on year, your potential earnings from it will not grow with it at remotely the same rate. That will only happen if and once you cross onto the other side, i.e. become a coveted Partner, which seems to take 10 years on average. If you make your startup succeed, some portion of your net worth will grow at the same rate at which you make the company grow. This builds wealth, and this is why working at a startup is very different, even financially. It’s not just where you learn the most and the fastest, but also it’s the highest leverage application of your energy and legal skills.

To summarize: if you have risk potential, and are looking to work in a fast-paced, ever-changing environment with the chance to create a lot of wealth in a short term by working your ass off, work at a startup.

[Bonus crypto side-note: There are new, emerging ways of capturing non-linearity as well. E.g., many crypto protocols pay their contributors in their native tokens. One could start a law firm that provides services to collect and create a whole portfolio of such tokens. Capturing the non-linearity in the same way venture capitalists do.]

[[Bonus bonus side note: With crypto, DAOs, and all new sorts of economic organization happening on the internet, suddenly there are whole areas of cutting edge legal innovation opened up. Never forget, before ESOPs were legislated into company law, it was the innovation of a single law firm. More on that here. ]]

How do you start making the switch?

In my experience, the first off-path job is the hardest to get since you’re fighting against everyone's suspicions of an outsider, in a space where you presumably don’t know many people in. Here’s a small playbook on how to spot opportunities that you could be a good fit for as a young lawyer, and get that first gig.

Picking the right space

The first step is to find a space in which your legal skillset, would be broadly required.1 Ideally, this is a space that (a) has many new startups starting, and (b) is highly regulated (payments, fintech, insurance, social networks, etc.) or operates in legal uncertainty (crypto, fantasy gaming, previously all sharing economy startups, etc.), and (c) you have some minimum interest in it which will allow you to do a good job of it. Highly regulated since there is lots of legal crap to work through which you’d be better suited to do than most other team members. Grey area startups work because they’d want someone around all the time whose opinion they can rely on as they build something out.

Narrowing down to companies of the right size

Once you zero down on a space, the next step is to find those that are the right size — depending on the kind of work you want to do. As a general rule, the smaller the company, the more generalized work you’ll end up having. So:

If you want to do a primarily legal job in the long term and just want to move into “tech” broadly, it’s marginally easier and you’ll have a broader set of companies to choose from. Any medium to large startup would work. Most of these startups will have more than 50 people, a few rounds of funding, and someone with a legal background already on the team, whom you should aim to work with directly.

If you want to over time reduce the legal work you do, and want a broader change in job, and doing a legal job is just to play to your strengths and start working at startups, then you should target very early-stage startups. One which needs help on the legal end, but can’t afford to engage a law firm, or hire a senior lawyer on a full-time basis, since they don’t have enough legal work to justify that cost either. Picking the right space is more important here since your competitive edge disappears if they don’t need anyone with legal background on the team in the first place.

Creating the right role for you

This is only relevant if you’re looking to venture beyond legal work down the line. The secret here is that unlike most traditional roles at law firms, etc., early stage roles (especially all non-engineer, non-design roles) at startups are illustrative at best. If they like you, they’ll be more than open to discussions regarding carve-outs and role expansions. Too many young lawyers have starry-eyed ambitions of transitioning via the more fancy-sounding jobs, “product management”, “strategy”, and “marketing manager”. These are the tier-1 corporate law firm job equivalents in the tech world. Lots of aspirants, and lots of competition, will generally lead to only fancily credentialed people getting the first cut. Unless you’ve done something before that’s highly relevant to one of these, you won’t even pass the resumé filter.

The key here is to obviously start with a role that is at least 50-75% legal, and the ability to explore projects & odd jobs with other teams you have an inkling about being good at, whenever you’re free (i.e. at least half the time). Once in, you want to first ace what you’re supposed to do and then get involved more and more there. Over time, reduce the legal proportion of your job, either by sticking it out (earn trust so you’re more in control of what you work on) or by switching out into roles at other companies with a role closer to the ideal. Rinse and repeat and in about 3 years you’ll be at your ideal position.

Finding the right person to talk to

Only talk to final decision makers i.e. founders. They’ll be doing most of the hiring anyway. Only they have the authority, and the confidence to take unconventional hiring bets, like how yours would generally be. Unlike the top people at law firms who probably get their mail printed for them, most CEOs and Founders read all emails that come to them. The problem is that everyone in tech already knows this so founders get a bunch of cold emails every day. The easy thing now is that there is more than enough advice available on how to write a good cold email to stand out, but the hard part is figuring out which advice is correct.

Some possible hacks

There are a few “hacks” to this, which if done earlier in time, will better your odds of standing out and making it. Some of them are:

Just start a startup: Right after, or event during college, take a punt at starting a startup. This is not just a hack at getting a job, but if you succeed, you directly get to do what you want to do for someone else anyway. Starting one is so hard that even doing a reasonable job is impressive to most other founders, and is broad enough to show proof of at least some non-legal skills. If you do an average job, the best case scenario is that it turns into some kind of small business, while the worst case scenario is you shut down and are able to get hired at a startup much better than you’d otherwise have managed to.

Start anything hard enough and do well: What founders hiring want to see is high energy and a high learning rate. If you start a podcast, a newsletter, a conference, or a journal, and succeed, this too would be adequate proof to better your odds. Anything qualifies as long as, (1) it's a hard and uncommon endeavor, (2) success therein relies on many non-legal skills (marketing, sales, writing, social media, etc.,), and (3) the end product is a top-quartile success.

Develop expertise in any one area of law: This is most relevant for those who want to continue lawyering, just within tech. Early-stage startups generally struggle to hire lawyers, because they end up optimizing for generalists. I don’t blame them, lawyers are expensive, and there’s not enough legal work for them to do the full time so they’re better off hiring someone who can help out in other ways and learn new things while on legal downtime. A way to bypass this requirement is to be a very impressive specialist, in the area of law relevant to them. This could be anything not too broad: sports law, fintech (become an RBI website sleuth), securities law (serial SEBI-related internship master), gaming law (this one may be already taken), etc. This too is hard, but if you want to be “too good to ignore” and want to make the jump when you’re under 25, you can take up the challenge. “Expertise” doesn’t mean becoming an authority in the field (although that would be even better), you just need to be among the most well versed in your +/- 1 age bracket, and ideally the only one on the job market.

Finding other lawyers in positions of responsibility: Remember you’re not the first one to have left law to join something in tech. LinkedIn wizardry will give you a list of many such people who were lawyers in a previous life or at least went to law school. I say “people” because I’m not only referring to founders, but also in-house counsels and early team members, who’d also be charged with looking out for the next set of people to hire to bring into the company. Before fully venturing out, trained lawyers do legal jobs at startups not just because that's what they already know, but also because a lawyer in tech is much more likely to hire them than just another hiring manager. It just happens to be that most lawyers in tech are doing legal jobs in tech. When you’re an outsider you want all the help you need. In this position, credentials matter, your alumni network matters, and your background matters too. It is not surprising that many lawyers who are now in tech got their first entry into the space by getting hired by another lawyer (either by doing law-adjacent things at “legal-tech” startups, working under a GC at a startup, or at a startup founded by a lawyer).

The hardest hack: finding someone to bet on you

Getting in touch with companies that have former lawyers as early employees or founders, doesn’t magically make you more hireable. It’s just a proxy for what you’re actually optimizing for — finding people who would want to bet on you. Finding these people who can hire you themselves is good, but getting anyone who has done all this before to do it is all you need. Just like how the world of law firms is small and incestuous, so is the world of startups. If you have anyone like this taking a bet on you, they’ll mostly be able to give you enough of a boost to get you on your own feet in the world.

It’s obviously easier for me to see this in hindsight, but this is the way I got started as well. Leaving something I was reasonably good at was obviously hard — so I got in touch with Akshay, the only other person from my law school who I was told had a similar journey, four and a half years after someone first recommended that I talk to him. Helping him out on side projects for the next couple of months gave me the best “in” into tech that I could try for, and the confidence to conclude that I’d make it somehow. Relationships with these sorts of “mentors” compound. After working on projects and helping with the little things on and off for 18 months, when Akshay’s next thing was going to kick off, I joined him and we’ve been working together ever since.

Finding someone like that should not be too hard for you. Check with your primary network, old classmates, and friends from law school, and run some LinkedIn magic and you’ll find networks of these kinds of people. There are many who are or were in the same boat a couple of months ago. Just in the last 6 months alone, some friends of mine made the switch:

Arpit Agarwal (NLUD ‘19): After spending two and a half years at AZB in the General Corporate team, Arpit quit to become Counsel and Chief of Staff for 2586 Labs.

Jalaj Jain (GNLU ‘22): Spent the last two remote years of college understanding crypto and web3, and eventually started his own legal consultancy in the crypto space after graduating.

KS Pradham (NALSAR '21) left S&R Associates within 6 months to work with the NEAR Foundation. Ever since, he started Crypto Capable and works with the NEAR bizdev team.

Prerana Reddy (JGLS ‘19): Spent two years litigating at Keystone Partners in Bangalore, before quitting to join Koo’s Platform Trust and Safety (Policy) team.

Sanjay Krishna (NLUJ ‘18): Left Khaitan after 2 years, to start up in the legal education space, eventually joining Quolum as a growth generalist.

Parting notes, starting notes

Thanks for reading till the end! In case this seems like a lot, it is. Making the switch can be hard, but it's far from impossible. This whole essay collectively gives 10 or so routes to actually transition. You do well at even one of them and you’re good to go. If you‘d want to connect with me, or any of the people or companies mentioned, do get in touch! You can write to me on Twitter or via email. All the best!

Legal skillset refers to the very basics — drafting and redlining contracts, understanding regulations, writing notices and managing risk based on these.